Here is a rewritten version of The Passion of Saint Eadmund in modern British English.

The Passion of Saint Eadmund, King and Martyr

The Dedicatory Epistle

A tranquil scene of an ancient monastery surrounded by lush greenery with a serene monk in deacon’s robes seated at a wooden desk

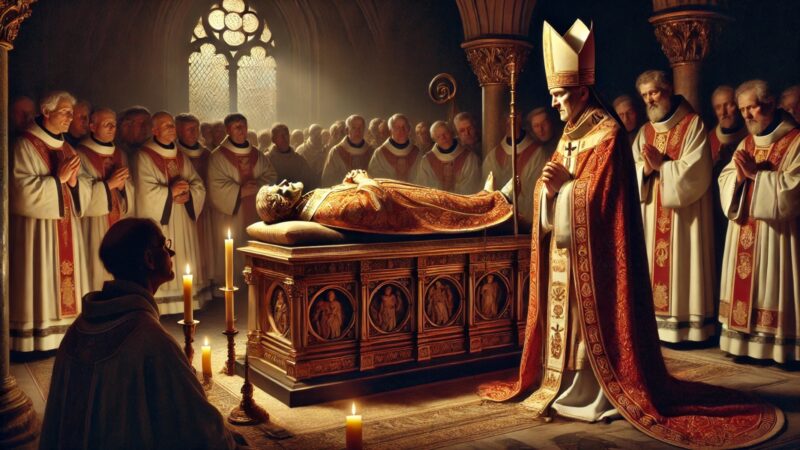

To Dunstan, Lord Archbishop of Canterbury, wise in age and character alike, I, Abbo of Fleury, an unworthy monk and deacon, humbly wish you the blessings of Christ. After departing from your gracious presence with great joy and returning to my monastery, I was approached by the brethren there. They earnestly requested that I write down the account of the martyrdom of Eadmund, King and Saint. They believed it would not only benefit future generations but also serve as a fitting memorial for English churches and a tribute to your holiness.

They were aware that the story had never been recorded before and that you, esteemed Archbishop, had recounted it, based on ancient tradition, to those gathered in your presence. Your account, shared with the Bishop of Rochester, the Abbot of Malmesbury, and others, moved all who listened. You had learned the tale as a young man from an elderly soldier, who had faithfully served as Eadmund’s armour-bearer on the very day of his martyrdom. With tears in your eyes, you described how his words had remained with you, treasured in your memory.

Thus, the brethren insisted that I preserve this story before it was lost. Despite my hesitation, I could not refuse their plea. So, setting aside other studies, I devoted myself to recording the virtuous deeds of King Eadmund, whose life on the throne exemplified true philosophy, and whose martyrdom revealed unparalleled faith and devotion.

In dedicating this work to you, I humbly ask that you correct any errors and omissions. The narrative follows your account as closely as possible, faithfully preserving the testimony of your venerable informant. May this work inspire others to venerate such a remarkable martyr. Farewell, my Father in Christ.

The Life and Martyrdom of Saint Eadmund

The Context of His Kingdom

A sprawling medieval landscape depicting East Anglia with rolling fields a fortified ditch marshlands and a distant coastline

In the distant past, three Germanic tribes—the Saxons, Jutes, and Angles—were invited to Britain as mercenaries. Initially, they defended the Britons against invaders but soon turned on their hosts, expelling them and claiming the land for themselves. They divided the island into kingdoms, with the eastern region, known as East Anglia, falling to the Saxons.

This fertile land was surrounded by natural defences—marshes to the north, the sea to the south and east, and a fortified ditch to the west. Within, it boasted rich soil, abundant forests, and rivers teeming with fish. Monastic communities thrived in its secluded marshlands, including those following the Rule of Saint Benedict.

The Reign of King Eadmund

A regal Anglo Saxon king seated on a wooden throne within a simple but grand hall surrounded by loyal subjects

Over this prosperous kingdom ruled Eadmund, a man of noble lineage and deep Christian faith. Though young, he was unanimously chosen by his people for his wisdom, humility, and virtue. Handsome and gracious, he displayed remarkable kindness to all, ruling with justice and compassion.

Eadmund balanced gentleness with strength. He was diligent in uncovering the truth and unyielding in the face of wrongdoing. Generous to the needy, a protector of widows and orphans, he embodied the wisdom of Scripture: *”Have they made you a prince? Do not exalt yourself, but be among them as one of them.”* His life of virtue invited the trials that God often allows for His faithful servants.

The Danish Invasion

A dramatic medieval scene of Viking longships arriving at a coastal village in East Anglia with warriors disembarking in chaos

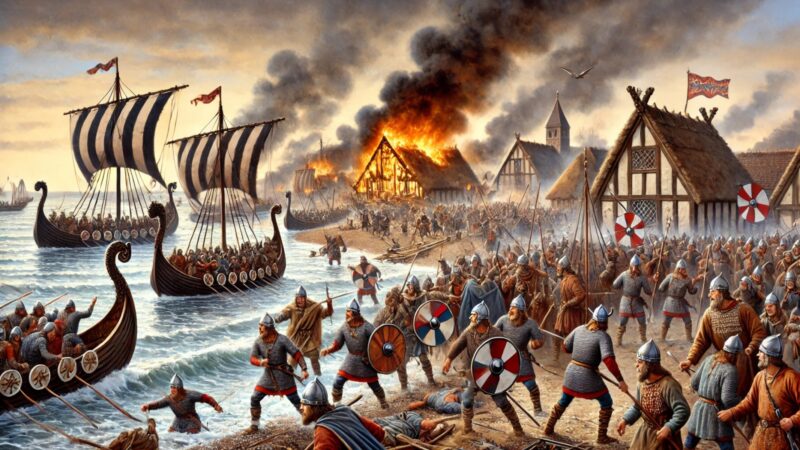

In Eadmund’s time, two notorious Danish leaders, Inguar and Hubba, ravaged Britain. These Vikings, known for their brutality, attacked Northumbria before turning their sights on East Anglia. Inguar’s fleet landed unexpectedly, sacking a city with merciless violence. Men, women, and children were slaughtered; homes were destroyed, and the survivors were left in terror.

After this devastation, Inguar sought out King Eadmund. Depriving him of allies and resources, the Viking intended to force the king into submission. Eadmund, however, refused to abandon his principles. When Inguar’s envoy demanded he surrender his treasures and rule as a vassal, the king responded with unwavering faith.

Eadmund’s Defiance

An Anglo Saxon king standing resolute in a simple royal chamber consulting a bishop dressed in religious robes

Eadmund consulted his bishop, who urged him to surrender for the sake of his people’s safety. Yet the king declared that he would rather die than betray his faith or forsake his duty to his people. He sent this message to Inguar:

*”I will not serve a pagan king. Take my treasures, but you will never have my soul. It is better to die for freedom and faith than to live in shame.”*

Enraged, Inguar ordered his men to capture the king. Eadmund was taken, beaten, and tied to a tree. The Vikings mocked and tortured him, shooting him with arrows until his body bristled like a hedgehog. Throughout, he called upon Christ for strength. Finally, they beheaded him and discarded his head in the forest.

The Miraculous Recovery of Eadmund’s Head

After the Vikings departed, Eadmund’s followers searched for his remains. Guided by miraculous signs, they heard his severed head calling out, *”Here! Here!”* They found it guarded by a wolf, which had protected it from harm. The Christians reunited the head with the body and buried them with reverence.

Years later, when Eadmund’s remains were exhumed, they were found incorrupt—his body untouched by decay, and his head perfectly reattached. A faint red line encircled his neck, marking his martyrdom. These miracles inspired great devotion, and a grand church was built to honour him in Bury St Edmunds.

Legacy and Miracles

A majestic Anglo Saxon church in a medieval town surrounded by villagers gathered to honour the newly constructed shrine of Saint Eadmund

Eadmund’s incorrupt body became a source of numerous miracles. Thieves who attempted to desecrate his shrine were struck down. A nobleman who arrogantly demanded to see the martyr’s body was punished with madness. Over time, the fame of Saint Eadmund spread far and wide, securing his place as a powerful intercessor and protector of the faithful.

To this day, Saint Eadmund is venerated as a model of Christian kingship and martyrdom, his life a testament to the triumph of faith over tyranny.

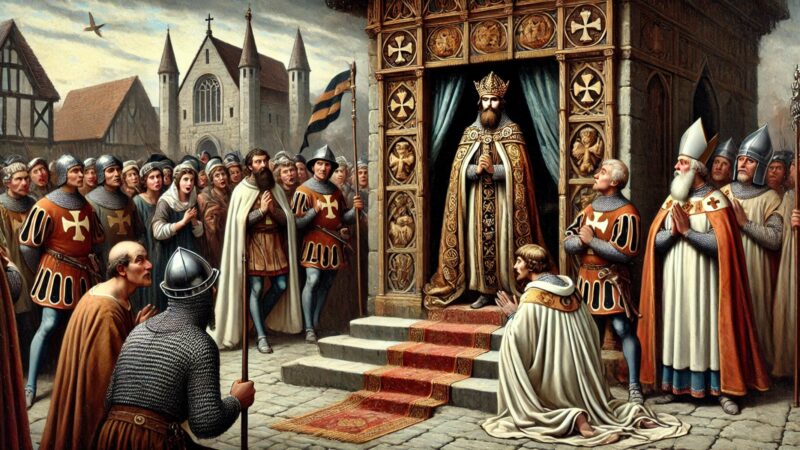

Punishment of the Nobleman

A medieval scene of a nobleman in luxurious robes surrounded by guards demanding the opening of Saint Eadmund’s shrine

“A man of great position named Leofstan, unable to restrain his impetuous nature, demanded to see the martyr’s body. Despite many protests, his authority prevailed. As the coffin was opened, the Lord struck him with madness, showing the gravity of his presumption. Cast out by his father, Leofstan descended into poverty and eventually perished, devoured by worms—an explicit punishment for his irreverence.”

Divine Punishment of the Thieves

A dramatic medieval church interior at night with a gang of thieves caught mid robbery frozen in place by divine power The scene is illuminated by

“Eight thieves, armed with tools, attempted to break into the church housing the saint’s remains. As they laboured to force entry, they were miraculously frozen in place. One hung suspended on a ladder, while others were immobilised in their acts of digging or filing. By morning, they were discovered and brought to trial. Although the bishop initially ordered their execution, he later repented, recognising the sanctity of the event and seeking God’s forgiveness for his severe judgement.”

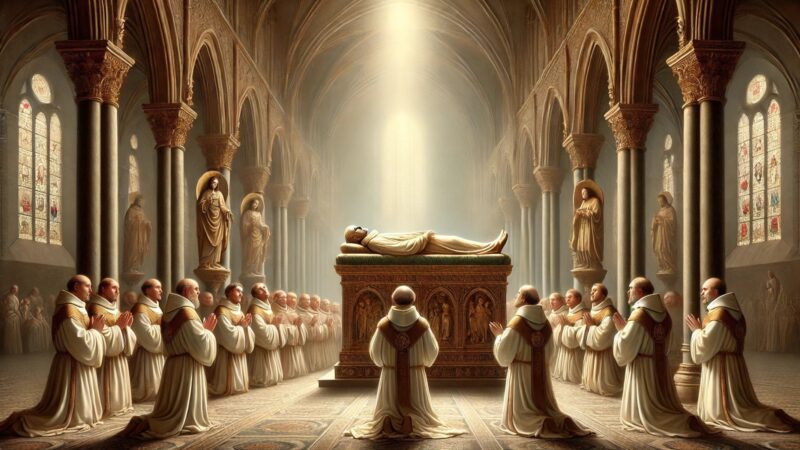

Saint Eadmund’s Incorrupt Body

A serene depiction of Saint Eadmund’s incorrupt body lying in state within a grand medieval shrine Monks and priests kneel in prayer while a faint

“Years after his death, Eadmund’s body was exhumed and found entirely whole, with no sign of decay. The severed head, once reunited with the body, showed no trace of its former separation, except for a faint red line around the neck. Oswen, a devout woman, tended to his remains, trimming his hair and nails regularly, which she preserved as relics. This incorruption was seen as evidence of his purity and sainthood.”

The saint’s incorrupt body became a source of great veneration, symbolising his eternal connection to divine grace.